A great deal has happened in frog land since the last blog, yet not much has really changed. The frogs still embark on their winter migration, threatened by a relentless highway, with one of the largest petroleum pipelines in the earthquake prone Pacific Northwest running beneath their breeding wetland. Plus, the local power company wants to carve off another ten acres of frog forest to widen a power-line cut. Happily, there’s also good news: Progress has been made in our search for a suitable place to build a forest breeding pond for amphibians. After monitoring six promising sites, and testing them in the hope they’ll have a fragipan four or five feet down, we now have a likely candidate. (Fragipans are very hard layerings of soil that restrict water flow and root penetration.) This winter we’re doing final testing on the site’s ability to retain water into July (when the pollywogs will be tiny frogs), under the amiable guidance of Kevin Foster — a geotechnical engineer who built his own pond several miles north on this same ridge — and who has been kind enough to volunteer his services. A new pond in a year or two is very possible. An invaluable help in getting to this point with this pond site was the discovery of a clause in the 1995 Forest Park Natural Resources Management Plan, a city statute, (NRMP - RE-11N - Newton Wetland Enhancement, page 171), which states that in the course of work done on Newton Road, this forested wetland was damaged, and for the sake of wildlife, should be “enhanced;” the door to a new pond in the Park suddenly open.

Even more exciting than a possible new breeding pond is the assembling of a team of biologists, engineers, ecologists, designers, and geologists — initiated by the Oregon Wildlife Foundation, and the Samara Group, and their respective directors, Tim Greseth and Leslie Bliss-Ketchum — has designed a tunnel to go under highway 30, with guiding funnels on either side of the highway to steer frogs, and other small animals, into a passage beneath the four lanes of rushing traffic. Much needs to be done before such a structure will be in place, but these sorts of connective projects are becoming all the rage, especially with more federal infrastructure money coming on line in 2025. (Dr. Barb Beasley has been a valuable resource, as she has built frog funnels and tunnels up in British Columbia. She splits her time between contracting work, and teaching courses in sustainable forest management and wetland ecology, with a specific penchant for birds and amphibians. She’s also active in SPLAT: Society for the Prevention of Little Amphibian Tragedies. Barb can be reached at wetlandstewards@gmail.com.)

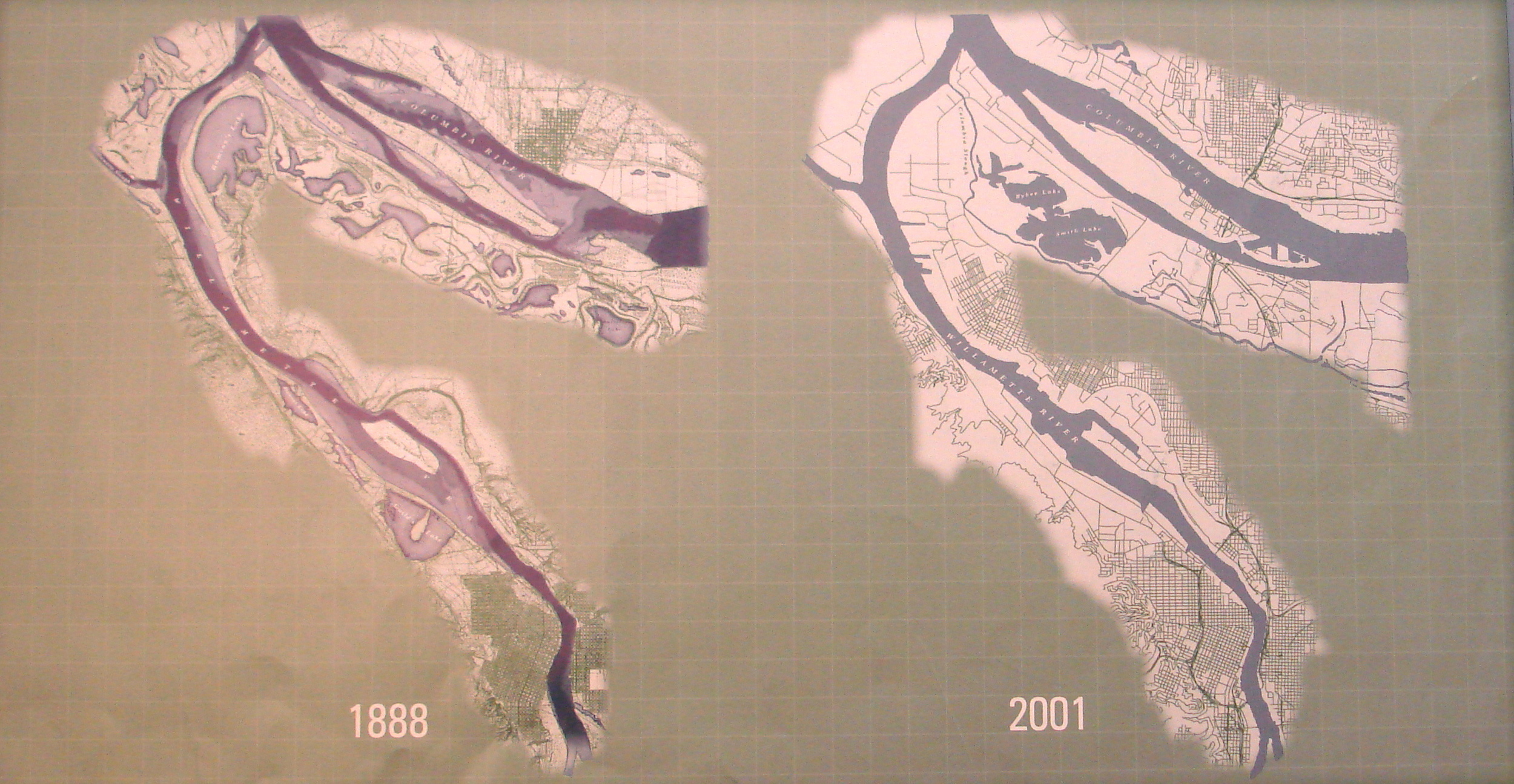

Hopefully both of these local frog projects will pass through planning and on to fund raising and building; with the new breeding pond, and a tunnel, the frog taxi will become superfluous. (This would be a very good thing, as a decade of catching frogs is, for many of us, enough, and more importantly, it’s much better for the frogs to make their own way, untouched. The retired herpetologist and researcher Dr. Marc Hayes told me rather pointedly that, if possible, the frogs shouldn’t be handled, which can elevate their rates of mortality through stress, and physical harm.) “Connectivity” — as in tunnels, overpasses and other corridors — is now all the rage, as it’s dawned on many of late that our automobile-fueled sprawling has reduced the landscape to green islands ringed by development; wildlife’s freedom of movement cut off from habitats they need for breeding, food, shelter, genetic diversity. Also, chopping the landscape into disconnected bits blocks the flow of natural processes that support clean air, rich soil, fresh water. A lack of connectivity leads to systemic breakdown, shrinking wildlife populations through habitat loss, degradation, fragmentation. Corridors that connect landscapes — like our tunnel, and a second tunnel, that will hopefully be built a couple miles up the highway — are real signs of hope, especially with the stresses of climate change becoming evident.

*. *. *

The “Covid Years,” 2020-2023, weird in America generally, were unusual in the Harborton frog world as well, both because frog numbers dropped precipitously, and our Covid precautions had a similarly alienating impact within our group as in society generally (meetings curtailed, masked in the dark, rainy nights, no end-of-season parties). Plus, the numbers of frogs caught plummeted from preceding years, but without a corresponding drop in the numbers of egg-masses; kind of a head scratcher, but unlikely to have anything to do with Covid. Our very first season, 2013-14, we caught 550 frogs going from the forest to the wetland, the numbers gradually increasing each year (though slipping to 433 in 2017-18), cresting at 1224 in 2018-19, and 2006 in 2019-20. Then from 2020 to 2023 the numbers were 423, 266, 376; yet the egg-mass number for that last year was 450, indicating the total number of frogs (male and female), coming down from the forest likely approached the high number of 1224 from 2018-19. What’s happening here?

Just as after three or four years of the taxi service the frogs began avoiding capture by flanking us, their next avoidance strategy may have been simply staying up on the steep hill until we left for the night, and then crossing the highway. Since the highway is mainly a commuter route, by 10 PM the traffic is a fraction of what it is at 5PM. Though it’s very boring for the poor folks who come out in the cold rain to catch frogs, only to wander amid no frogs for hours, it’s terrific for the frogs: they can simply hop to the wetland, likely without being run over, and seek out a mate. I’ve tried to catch the frogs in the act late at night, and early in the morning; nights when the conditions were good for migration (above 45 degrees and raining), and didn’t see one frog. Avery Marvin, one of my crew members, came later one promising night, after the rest of us had left. Frogs didn’t come out while Avery was there. but curious, she examined the nearly vertical slope with her head lamp, and found 11 frogs, sitting quietly amid the ferns. Each frog was motionless, watching from a vantage point from which they had a clear view of the road below, where we headlamp Cyclops's wander. Who knows how many frogs were further up the slope, waiting for the coast to clear?

And now another surprising population and gender question mark: This past February we caught over 1570 frogs, only 144 of them clearly female, and the vast majority of them quite small; 2-2 1/2 inches long. Their small size indicates they’re two years old, and it’s likely their first breeding year. We may have made the mistake of assuming small frogs were all male, since the males are generally smaller than the females, and we’ve gotten used to assuming the little guys are males. But toward the end of the month it was noticed that some of the small frogs were gravid, and didn’t have nuptial pads (long thumbs on their front feet indicating they’re male). The tiny frogs are hard to handle (there’s not much to hold on to, and they’re strong and squirming), so it’s a job to sex hundreds on a busy night by examining for nuptial pads. Plus, we’ve never been swamped with little guys like this. What also makes this striking is the year when most of these guys hatched out was two years ago, 2022, when we only caught 266 total frogs going down to the wetland. Far more frogs than that may have made their way to the wetland late at night, or predation may have been far less intense that summer (the numbers of visiting Great Egrets, for instance, has varied from just a few to as many as 27). Or perhaps the more mature frogs — having learned to avoid us — came out after our roving headlamps were gone, and we caught mostly the rookies, who haven’t yet learned to be wary of us.